The Perfect Crime Is Possible

The Perfect Crime is Possible

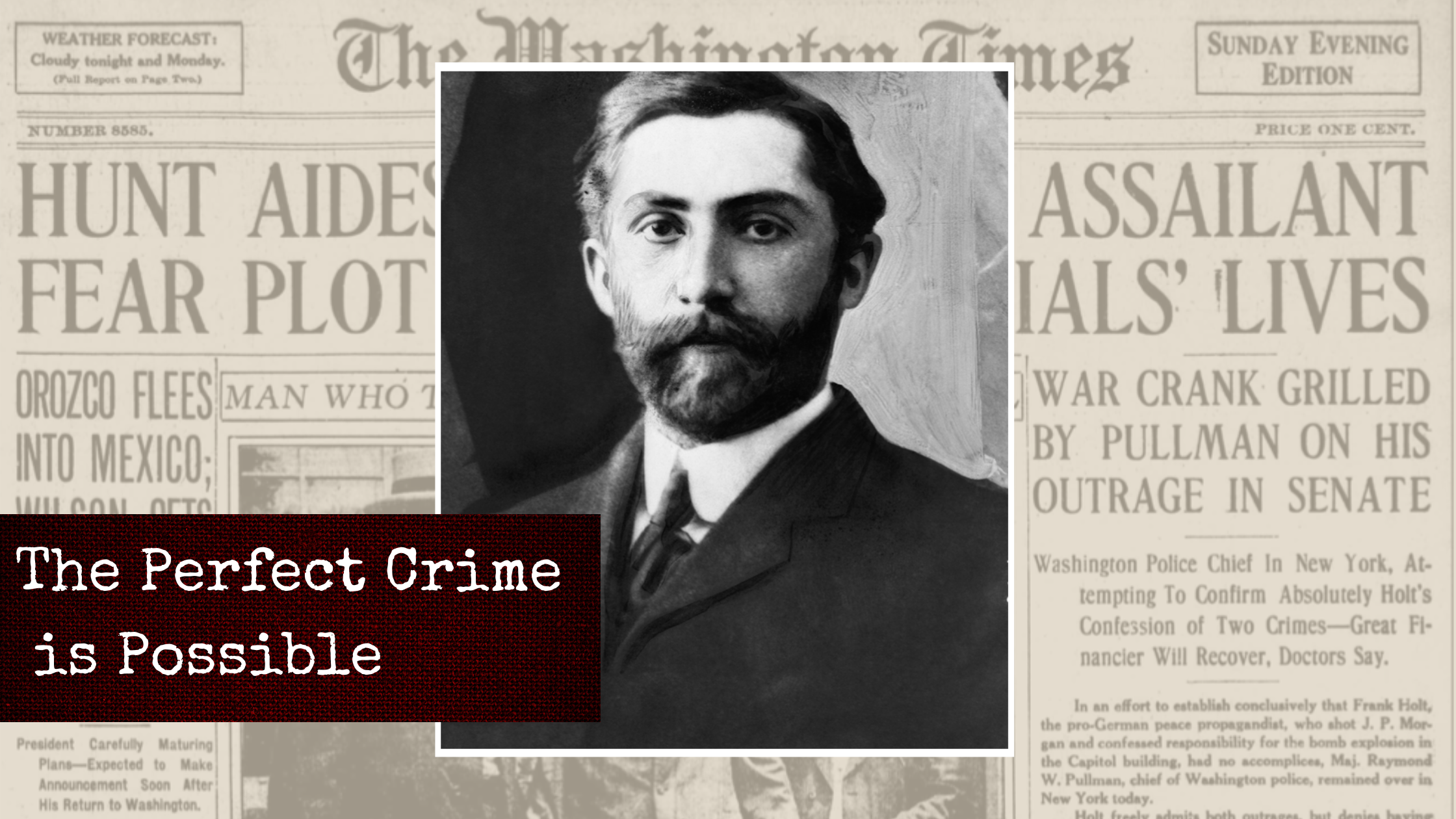

Erich Muenter (aka Frank Holt) was the Harvard professor and wife murderer recruited by the German network of spies as an assassin to bring down vital targets such as ships, factories, livestock, and even captains of industry like J. P. Morgan during World War I. Below is an excerpt from my book Dark Invasion: Germany's Secret War and the Hunt for the First Terrorist Cell in America, revealing how Muenter came to discover that the perfect crime is possible.

If Erich Muenter hadn’t walked across the Harvard campus to Emerson Hall on that wet February day in 1906 to borrow a book, he would never have seen the student pull the short-barreled black revolver from his pocket, aim, and, just as his arm was grabbed, fire. And then things might have been different.

It had been raining all morning, but as Professor Muenter made his way from the tiny classroom where he taught German to the formidable redbrick building on the opposite side of the muddy Harvard Yard, the storm suddenly became torrential. He tried to hurry, but his condition—“tuberculosis of the bones,” the doctor had diagnosed with a helpless finality—made walking even in the best of weather an awkward exercise. By the time he reached the pillared portico of Emerson Hall, he was soaked.

“What is man that Thou art mindful of him?” challenged the inscription carved above the massive entrance doors. Charles Eliot, the pious Harvard president, had personally selected the lines from the book of Psalms only weeks before the building had opened to students the previous year. But Muenter held little countenance for religion or, for that matter, any philosophy that questioned his rightful place in the scheme of things. He bristled with an egotist’s combative certainty; humility never had a chance to take root.

This dismal afternoon Professor Muenter’s always feisty, self-important attitude—a demeanor that famously filled timid Harvard undergrads struggling through German 101 with fear and anxiety—was further sharpened by the fact that he was drenched. The best Muenter could do, though, was to slap his damp, center-parted brown hair into place, give his shabby Vandyke a restorative tug or two, wipe his wire-framed glasses dry, and try to fix his customary confident, bemused expression on his sallow face. He might be soaked to the bone, but he’d still make it clear that he was a man of whom anyone, even the Harvard president himself, would be wise to be mindful.

The long trek up the three winding flights to the university’s new psychology laboratory was difficult; his spindly legs, the muscles weakened by his degenerative illness, didn’t do well on stairs. But Muenter was determined. At an off-campus German Society gathering he’d recently made the acquaintance of the lab’s director, the celebrated professor Hugo Munsterberg, and the two men quickly found they had much in common.

It didn’t seem to matter that Muenter, thirty-five years old and as thin and boyish as an undergraduate, could easily have passed for the portly forty-three-year-old bald-headed professor’s son. Nor was their bond simply that they both had been born in Germany, still savaged their English with a distinct guttural rumble (although the younger man’s accent was significantly fainter; after all, he’d been living in America for nearly half his life), and that both proudly held a cherished, even on occasion reverential, allegiance to the Fatherland. Rather, their budding friendship was built on a deeply held common interest in the criminal mind.

Professor Munsterberg had come to Harvard at the urging of William James, the philosopher, to set up the first scientific laboratory in the nation to explore the psychology of crime. And while Muenter’s bachelor’s degree from the University of Chicago was in German, as a graduate student at Kansas State University he had investigated the motives (or more often rationales, he’d correct with a sly precision) that drove individuals to commit crimes. His research had resulted in a paper entitled “Insanity and Literature.” Now at Harvard, although he was pursuing his doctorate in German literature, Muenter retained his fascination with the mental mechanisms that create criminals.

When Muenter explained all this to Munsterberg, the professor immediately invited the younger man to visit his lab and to borrow any books he wanted from his personal library. Today, undeterred by the weather or the climb, a curious and enthusiastic Muenter had come to take advantage of the professor’s generosity.

What a world Muenter entered! The top floor of Emerson Hall was a warren of rooms through which wound a snaking trail of electrical wires connected to ingenious machines that, Munsterberg boasted, could do nothing less than “reveal the secrets of the human mind.”

As christened by the psychologist, the devices included an “automautograph,” to measure arm and finger muscle movements under stress; a “pneumograph,” to measure variations in breathing caused by emotional suggestions; and a “sphygmagraph,” to record the halts, jumps, and rapid beatings of a guilty heart. These machines, Munsterberg promised, “reduced a knowledge of the truth to an exact science.” In fact, in a widely read interview published in the New York Times, a resolute Munsterberg had proclaimed that “to deny that the experimental psychologist has the possibilities of determining the truth-telling powers is as absurd as to deny that the chemical expert can find out whether there is arsenic in the stomach.”

Months later, when questioned about Muenter’s tour of the laboratory on that rainy day, the professor would also be reminded of his bold comment to the newspaper—and his choice of metaphor would come back to haunt him with a chilling prescience. But that afternoon the renowned criminologist had no suspicions. In fact, he invited his young friend to sit in on a class that was about to begin.

Muenter was standing in the back of the lecture hall, listening to the professor with interest, when the outburst occurred.

“I want to throw some light on the matter,” a student interrupted, rising to his feet as he spoke.

All at once another student jumped up to challenge him. “I cannot stand that!” he shouted.

“You have insulted me!” the first student angrily replied.

“If you say another word—,” the second student warned, clenching his fist.

The first student drew a short black revolver from his coat pocket. In a fury, the other student charged at him.

At the same moment, Professor Munsterberg hurried from behind his lectern, managed to put himself between the two students, and grasped the gunman’s arm.

Suddenly the gun went off. Clutching his stomach, one boy slumped to the floor.

The classroom was pandemonium. Shrieking students jumped from their seats, eager to escape. But Erich Muenter, it was observed, stood rigidly at the back of the room, watching all that went on around him with a calm, unruffled fascination.

Nor did Muenter show any reaction when in the next instant the “wounded” student, grinning broadly, dramatically rose to his feet.

Calling the astonished class to order, Professor Munsterberg instructed the students to write an exact account of what had just happened. Tell me precisely what you saw, he reiterated.

As the students wrote, their professor explained that this was an exercise to demonstrate the fallibility of even eyewitness testimony in a criminal case. The search for truth, he lectured, may be well intentioned, but memory is always subjective. The shrewd courtroom defense attorney can use the power of suggestion to defeat most attempts to get at the truth. Similarly, the professor went on, the expert criminal can manipulate people so that they’ll believe what he wants them to believe.

When the students read their reconstructions aloud, it was clear that Professor Munsterberg’s thesis was correct: no two students offered identical versions of the “shooting.” And when the psychologist tried to influence their memories with his own probing questions, their recollections grew further distorted. “Truth,” the professor concluded, “exists only as an invention created under the spell of belief.”

That evening as Muenter—clutching the borrowed book, its specific title long forgotten—made his way back to the rooms he shared with his pregnant wife and their daughter on Oxford Street, he found himself still thinking about all he’d seen. Time after time he played back in his mind the demonstration he had witnessed, and the students’ contradictory and easily manipulated recollections of events. It had been an education.

But there was another reason the demonstration held his thoughts. It confirmed his long-cherished theory that the perfect crime was possible. Cast a “spell of belief,” and you could get away with anything. Even murder.

Full of drama and intensity, illustrated with eight pages of black and-white photos, Dark Invasion is riveting war thriller that chillingly echoes our own time. You can order your copy here.

Critical Acclaim for Dark Invasion:

★★★★★

“Howard Blum’s riveting and perturbing Dark Invasion…is well-researched and written, and it maintains a fairly high level of suspense, which is difficult to bring off in a book about historical events.”

—Wall Street Journal

★★★★★

“Dark Invasion…will move you to the edge of your seat with the facts alone, but the author’s suspenseful detective-mystery narrative is what keeps you there.”

—USA Today

★★★★★

“Blum briefs us on early homeland security with tales of German terrorists, including military officers, a germ-warfare expert, a Harvard prof and a document forger.”

—New York Post, “Required Reading”

★★★★★

“Dark Invasion is a must-read for lovers of suspense and anyone who wants to understand how the basis of our homeland security system was born.”

—Tom Reiss, author