Russian Code-Breaking and Cryptography During the Cold War – In the Enemy’s House

Cryptography, Post World War II

This method of code breaking and deciphering may have changed with the onset of the Internet and modern technology, but the approach remains the same.

In this excerpt from In the Enemy’s House, I walk through the hypothetical stages of how a Russian spy might communicate—and how a cipher clerk might be able to decode that message. This is the technique in which the US worked backwards to capture Russian spies during the Cold War era.

Code-Breaking, In the Enemy’s House:

The system worked, in its plodding, laborious, and seemingly foolproof way, basically (and hypothetically) like this:

A Russian spy, call him Paul Revere, came in from the cold to the New York rezidentura (as the Soviet diplomatic missions were known) with an important message that needed to reach Moscow without delay: “The British are coming.”

The cipher clerk grabbed the message from the secret agent and jumped into action. Like a diligent copy editor, he smoothed Paul Revere’s unpolished prose, taking care that it conformed to all the elements of style that had been drummed into him in cipher school.

He must, he knew straight off, disguise the source. The security-conscious KGB prohibited the mention of an agent’s actual name in a cable; only aliases could be transmitted. So the dutiful clerk checked a top-secret list for Revere’s code name. He found it: Silversmith.

The rest of the brief message needed some sprucing up, too. There is no “the” in Russian; the article is a notion alien to the language. Also, verbs were often deleted in cables, the logic being that they were implicit and only slowed down the recipient’s unbuttoning of an urgent message. Finally, per another stylistic convention, certain nouns with Western national and ideological affinities, such as “British” (or, say, “CIA” or “FBI”), were replaced with an insider’s jargon, a practice rooted more in a jaunty spy fellowship than any security concerns. Thus, “British” became “Islanders.”

The edited message the clerk transcribed on his work sheet—the verbs deemed necessary—now read: “Silversmith reports Islanders coming.” (Of course, KGB-trained clerks wrote in Russian, using Cyrillic characters; this example, for clarity’s sake, is playing out in English.)

With the editing of the plaintext—i.e., the original message—completed, the clerk was ready to take the codebook out of the safe.

The codebook was a secret dictionary that allowed the members of the club—in this case, KGB officers—to communicate with fellow clubmen without outsiders being able to understand. It was employed to translate the information into the secret language—to encode it.

The club’s shared covert language was numerical. Words, as well as symbols and punctuation, and often entire phrases, were reduced to four digits. If a word was not in the KGB’s dictionary—an American family name or some abstruse scientific term, for example—then there was a prearranged way to handle that, too: a specific four-digit number was employed to announce to anyone in the club receiving the message, “Here’s where we’re going to begin spelling an untranslatable word.” Next, the word would be spelled out in Roman letters, with two-digit designations for each letter taken from a “spell table” that was an appendix to the secret dictionary. And, finally, to indicate that this strange (at least to a Russian reader) word was completed, there’d be another specific two-digit number—the “end spell” code.

Working carefully, checking and rechecking each word in the codebook, the code clerk would soon have come up with a translation:

Silversmith reports Islanders coming

8522 7349 0763 6729

Next was another small but crucial security measure. The four-digit dictionary words were transformed into unique five-digit numbers by a simple bit of hocus-pocus: the initial digit of the second four-digit group was tacked on to the end of the first group, and so on, the immediately subsequent digits moving forward until each group was now five numbers. However, for the final unit, the remaining digit would become the first number of the original last word. The clerk’s worksheet would now read like this:

Silversmith reports Islanders coming

85227 34907 63672 96729

And with this, the first lock on the door had been turned: the message had been encoded.

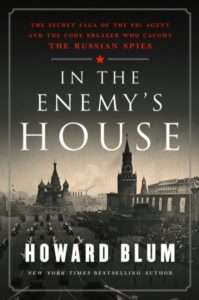

Order Your Copy of In the Enemy’s House

Discover more about how Meredith Gardner and Bob Lamphere uncovered a ring of Russian spies during the Cold War as they worked on operation Venona, a top-secret mission to uncover the Soviet agents and protect the Holy Grail of Cold War espionage—the atomic bomb. A breathtaking chapter of American history and a page-turning mystery that plays out against the tense, life-and-death gamesmanship of the Cold War, this twisting thriller begins at the end of World War II and leads all the way to the execution of the Rosenbergs—a result that haunted both Gardner and Lamphere to the end of their lives.

Order your copy today.

“The spy hunt set off by the Venona decrypts is one of the great stories of the Cold War and Howard Blum tells it here with the drama and page-turning pace of a classic thriller.” (Joseph Kanon, bestselling author of Defectors, Leaving Berlin, and Los Alamos)

“Blum has managed to provide a fresh look at the familiar story of the Rosenbergs. Indeed, his book may be the last piece we need to understand the puzzle surrounding one of the most memorable espionage cases of the 20th century.” (Ronald Radosh, New York Times Book Review)

“In a time when our nation is worried about Russian influence Howard Blum brings us a page turning history of how the FBI and the forerunner to the National Security Agency ultimately tracked down the Soviet spy rings operating in America. The book reads like the best of the spy novels. His heroes are FBI agent Bob Lamphere, a hard-drinking kid from Idaho and code breaker Meredith Gardner, a nerdy language expert from Mississippi. In these two people we have a very successful integration of human intelligence with signals intelligence.” 5-Star Amazon Review, David Shulman